Monstrous seasonal monsoons are two weeks overdue. They hang heavy overhead, sit thick in the Congolese air. It is 4:00 a.m. in the jungle, primetime in the US, and Muhammad Ali is in the middle of the ring, glowing. He bounces and punches at the air in a white silk robe—‘For he is the Prince of Heaven,’ says journalist Norman Mailer, and he floats and he shines. It’s hot. Muggy. The stadium is a corrugated tin shed that traps the steamy air and literally rumbles with noise and light. Ali jumps up on the ropes and conducts the baying, ecstatic crowd through a chant of ‘A-li! Bomaye! A-li! Bomaye!’ And here comes Heavyweight Champion George Foreman and the noise reaches a decibel level that didn’t seem possible. The bout’s narrative tension melts and weaves together with the humidity and you could cut it all with a good punch. The rain has been a long time coming. The fight has been a long time coming too.

And now, in full view of the match officials and Foreman’s sizable entourage and the cameras beaming live footage to one billion people around the world, Ali’s coach methodically walks from ring post to ring post with a toolbox, loosening the ropes.

‘Ali! Bomaye!’ means ‘Ali! Kill him!’ in Lingala.

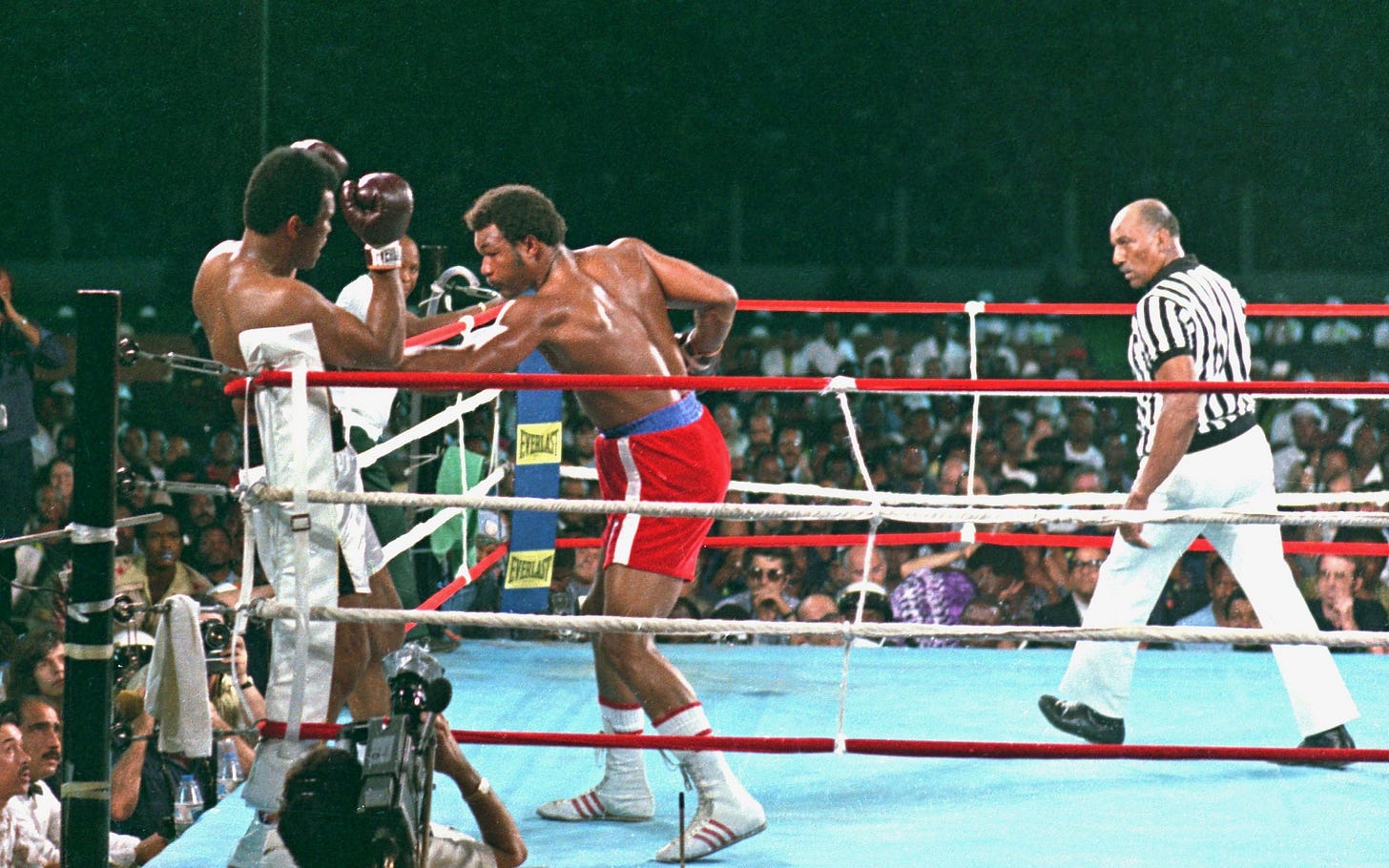

Can you even hear the starting bell ding once over the roar? Do you see Ali dash over and dart back, dancing and ducking and bam! A fist in Foreman’s face. Then they clinch. Wrestle. Headlock. Pulled apart. Bouncing. Left, right, wrestle again. More bouncing. Foreman stunned by speed in the dead centre of the canvas. Ali bops butterfly-like all around him, red leather gloves stinging, zipping into flesh. Roars from the grandstand at every punch. Humidity: Impossible. Lights: Burning. Foreman and Ali entwined.

‘A-li! Bomaye! A-li Bomaye!’

Ali is electric for an entire minute, but this jungle heat is for real. It takes whatever energy you give. Ali only lulls long enough to, like, breathe, but that’s enough time for Foreman to find his humongous feet. He takes big steps, meaningful steps, in the Prince of Heaven’s direction, chasing him into the corners. Foreman now fangs ferocious, heavy punches with his enormous frame, he launches big meaty missiles from distance. Whenever they get close, Ali will wrestle, pushing down hard on the champ’s neck and yelling, ‘That's all you got, George?’ into the thick sticky dawn.

And look, Prince of Heaven or no, Ali’s gift of the gab notwithstanding, George Foreman is just simply not the kind of guy you should taunt under any circumstances. He is 6’4” and 100kg flat. They call him “Big George” for a big reason. Of his 40 professional boxing bouts to date, he has ended 37 of them with a technical or a literal Knock Out. On his ascendent run to the heavyweight title he knocked the incumbent Joe Frazier to the floor six times in six minutes. He is 25 and his punches have a ‘sheer power,’ they are ‘greatly feared,’ Mailer says they ‘...hit in such a way that the nucleus of his opponent’s will was reached. Fission began. Consciousness exploded. The head smote the spine with a lightning bolt and the legs came apart like falling walls.’ Yeesh.

So you can see that whatever Big Geroge lacks in technical nous he more than makes up for in presence. He is now seemingly everywhere in the fight's opening round, never more than a swinging arm away from the Prince, taking one step for every two of his contender.

Running from danger is a primal human urge. Boxing understands this—that’s what the ropes are for. Faced with a formidable foe, and already fatiguing in the heat and humidity of the Congo, late in the first round Muhammad Ali deploys a tactic that is so fundamentally against our in-built, limbic human nature that it is both profoundly stupid and extremely brave.

The Prince of Heaven leans back on the ropes and lets himself get punched. Ali calls this the ‘Rope a Dope,’ and he does it more and more through rounds two, three and four.

At the age of 32, Muhammad Ali has lived a full and complex life—an interesting mix of violence and peace that has made him one of the world’s most famous people, a cultural as much as an athletic champion to the local Kinshasa fans. His glittering amateur career, Olympic Gold Medal, and astonishing early success was punctuated (punchuated?) with his trademark trash talk. Ali ran his mouth. He said Sonny Liston was ‘Too ugly to be world champion,’ and quickly followed it up with ‘I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived!’ Though otherwise lethargic in training, Ali had come alive when talking to the press. He read his poetry. He called Big George ugly and slow. He said he would ‘float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.’ He said, ‘I’m so fast—last night, I turned the light off, I was in bed before the room was dark.’

This, as much as any punch he ever threw, was what made Muhammad Ali so loved and hated. A fast talking, loud mouthed young black man made a mockery of the White Establishment in one of the most racially charged periods of American history. When he conscientiously objected to the Vietnam War in 1969, then aged 27, he was stripped of all his titles and systematically denied a licence to box anywhere in the United States.

‘Man I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong,’ he said. ‘Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while [my people] in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?’

So this fight really has been a long time coming for Ali, and it's palpable. There is pressure in the air. It has been eight long, hard years for the Prince of Heaven to get to this title fight, to ride years of backlash and detention for refusing to go to war, to finally be awarded licence to box again in the twilight of his career, to painfully work his way back up the ranks he so magnificently blitzed at 22. All of this hangs impatiently above the fight, thick and fused with the monsoonal rain.

Can you hear the roaring of the crowd start to waver in the fourth round, as Ali sinks further and further into the ropes? Can you see the faces of his fans start to think that he might not only lose but could possibly even die? Can you feel Forman rain hundreds of thunderous, murderous blows down upon the Prince? Can you hear Ali, whenever he has enough air in his lungs to breathe, call George Foreman weak and a wimp and beg him to throw more punches?

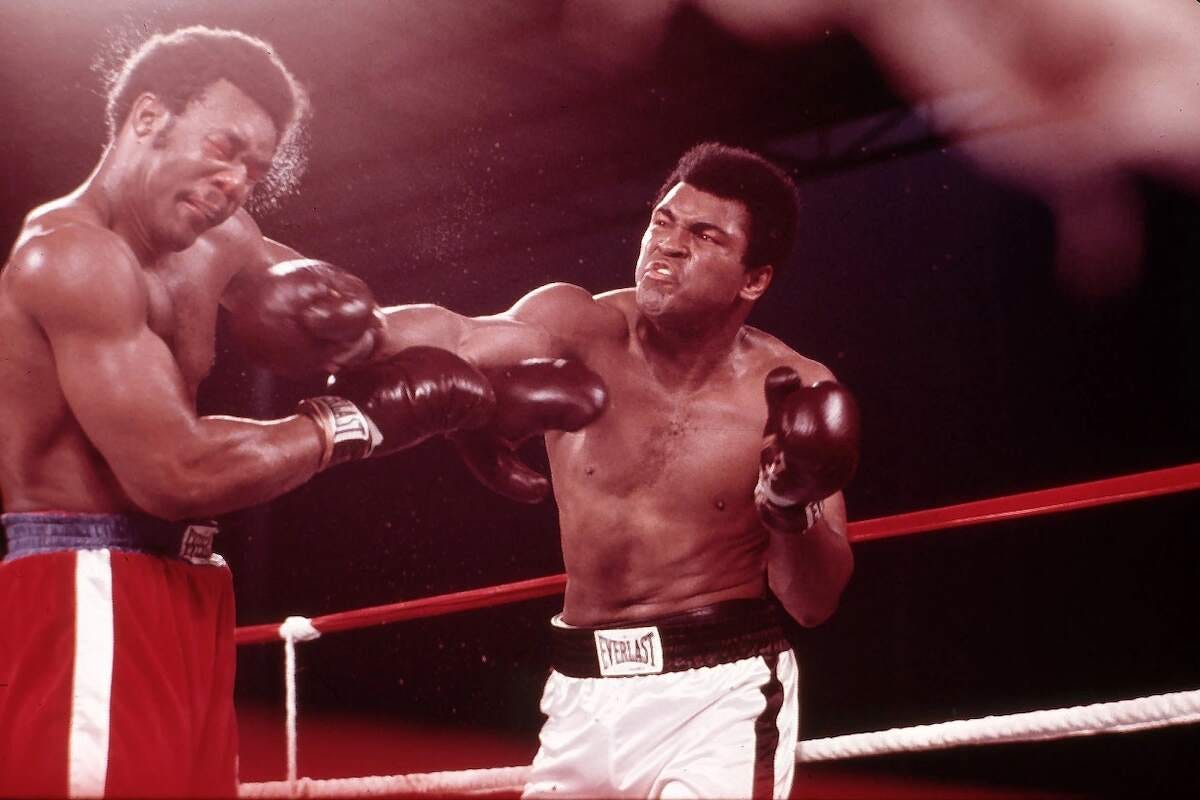

By round five it’s Foreman that looks gassed. By round six he is totally exhausted. ‘They told me you could hit, George!’ Ali yells. ‘Can’t you fight harder? That ain’t hard!’ The best puncher in the world, the man mountain with nuclear hands, struck Ali again and again in the kidneys, the ribs, the arms, and the head. He launched barrage after barrage of heavy maniacal slamming punches, breathless blasting bombs to the body. By round seven, Foreman is just listlessly swinging, as hard and heavy as he can muster in the heat. With a left-right combination he strikes Ali hard in the jaw, the best punch of the night, to which Ali says, ‘Didn’t hurt a bit.’ They get close enough to wrestle and Ali pulls on Foreman’s neck, whispering in his ear, just for him, ‘That all you got, George?’

Still Ali waits. The Prince of Patience. The Prince of Getting Punched, absorbing wave after wave of explosive wallops, sunk back into the ropes. Sunk into his plan and his destiny. Waiting. Eight rounds and eight long years he’s been waiting, heavy with the purpose of a cloud about to rain. Foreman is floppy, Ali is firm. Foreman’s face is puffy and Ali’s is bright and eager, you can see him smile in the gap between his gloves.

Late in the eighth, Ali throws out a glove. Pop. He’s been doing this every now and then throughout the fight, but this time it makes good contact with Foreman’s chin. Big George seems confused by it more than anything, and steps back to work it out. This is the window Ali was waiting for. All of a sudden he comes to life, glittering in the light, dancing beneath the beams. He fires a few quick serious shots across the bow, and then the big one.

As Mailer describes it: ‘A big projectile exactly the size of a fist in a glove drove into the middle of Foreman’s mind, the blow Ali saved for a career. Foreman’s arms flew out to the side like a man with a parachute jumping out of a plane, all the while his eyes were on Ali and he looked up with no anger as if Ali, indeed, was the man he knew best in the world and would see him on his dying day. Vertigo took Geroge Foreman and revolved him…down came the champion in sections and Ali revolved with him in a close circle, hand primed to hit him one more time, and never the need, a wholly intimate escort to the floor.’

The light of a new dawn rolled through Kinasha. Muhammad Ali yelled into the first microphone he could find, ‘I told y’all I’m the greatest of all time, I showed you tonight I’m still the greatest of all time.’ The delirious crowd, the local Ali faithful, rushed into the streets, celebrations erupted around the world. Then came the rain. That very morning. Two weeks overdue. The storm finally broke and thundered down in buckets. Tropical rain so heavy, monsoons now released so overdue, that it flooded the whole stadium, gushing through the aisles, sweeping chairs off downstream, and washing away the very ring that only hours before had hosted one of the greatest boxing matches of all time.

Muhammad Ali laughed the next day, bruised, buoyant, and offered to take credit for holding back the rain.

My new status as a commuter is perfect for catching up on these.

I remember the fuss about this. And there was a song , In Zaire

A ripper! Thank you!